Elements

Release 1.7.1

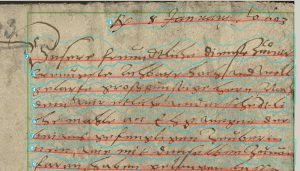

For handwritten text recognition (HTR), automatic layout analysis is essential – no text recognition without layout analysis.

The layout analysis ensures that the image is divided into different areas, those that do not need further attention and others that contain the text to be recognized. These areas are called “Text Regions” (TR, green in the image). Transkribus needs “Baselines” (BL, red in the image) to recognize characters or letters within the text regions. They are drawn underneath each text line. Baselines are surrounded by their own region, which is called “Line” (blue in the image). It has no practical relevance for the user. The three elements Text Region – Line – Baseline have a parent-child relationship to each other and cannot exist without the respective parent element – no baseline without line and no line without text region. One should know these elements, their functions and their relationship to each other, especially if you have to work on the layout manually.

Manual layouts should rather be an exception than the rule. For most use cases, Transkribus has an extremely powerful tool – the “CITlab Advances Layout Analysis”. It is the standard Transkribus model that has been used successfully since 2017. In most cases it delivers great results in automatic segmentation. This automatic layout analysis can be used for a single page, a selection of pages or an entire document.

All elements for segmentation can also be set, modified and edited manually, which is recommended in more complex layouts. An extensive toolbar is available for this purpose.