Textregions

Release 1.7.1

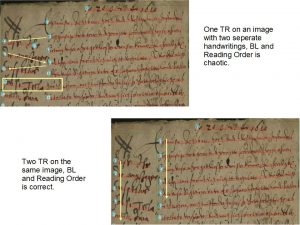

Usually, the automatic CITlab Advanced Layout Analysis in its standard setting will recognize a single Text Region (TR) on an image with the corresponding baselines.

However, there are also simple layouts where the use of several TRs is recommended, e.g. if there are marginal notes or footnotes and similar recurring elements. As long as these text areas, which differ in content and structure, are contained in a single TR, the layout analysis simply counts the lines from top to bottom.

This “Reading Order” does not take into account where a text actually belongs in terms of content (e.g. an insertion), but only where it is graphically located on the page. Correcting an automatically generated but unsatisfactory Reading Order is boring and often time-consuming. The problem can easily be avoided by creating several text regions in which the related texts and lines are well kept like in a box.

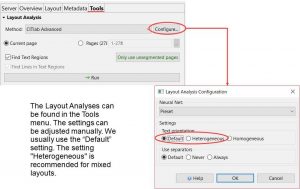

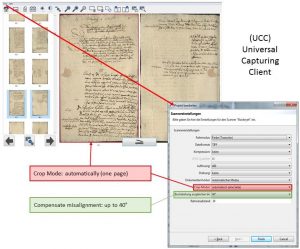

To do this, you create the TRs manually at the appropriate places. Afterwards start the line detection with CITlab Advanced to add the baselines automatically.

Tips & Tools

If you have drawn the TRs manually and want to have the baselines drawn automatically by CITlab Advanced LA, you should first uncheck the box “Find Textregions”. Otherwise the manually drawn TRs will be replaced immediately. You should also make sure that none of the individual text regions is activated, otherwise only these will be edited.